January 30, 2023

SLAS2023 Keynote Speaker and national bestselling author Sam Kean serves up the best and worst moments in science history, seasoning it with a bit of humor. Get a sneak preview of his upcoming presentation as he discusses the marvels of forging ahead in modern science by examining its roots.

“I love science and for a long time I thought I was going to be a scientist,” says Kean. From his uncertain start in the lab during his undergraduate years while studying physics and English at the University of Minnesota, to traveling the world collecting stories for his latest book, he pursues science with zest and hopes to capture that for others.

His subject matter has uncovered everything from neuroscience, genetics and medical ethics to a history of the air we breathe – which includes sextillions of molecules that enter and leave one's lungs every moment – and a World War II adventure story about the people united to stop the Germans from developing an atomic bomb. He has watched archeologists reconstruct elaborate feasts, ancient boats and catapults. While his research approach changes from book to book, the common thread is making certain that the story is something that people want to read.

“All the things that go into a good science story are the things that make it a good story, period,” Kean comments. “If I want someone to invest the time and energy to read an entire book of mine, I want them to think that this is an incredible read. These stories have intriguing characters, conflict and drama.”

One such story, which holds all of these elements, is that of sinister World War I German scientist Fritz Haber, creator of a process that takes nitrogen from the air and turns it into ammonia – used to make chemical fertilizers. Estimates are that half the people on Earth would not be here without Haber’s discovery for mass producing fertilizer. However, what was gained was also lost as the same process was used in the German gunpowder industry. Haber also took a toll on the human population by developing the deadly gases used during both World Wars.

“Sometimes you find scientists doing heroic things and then you find villains. It’s rare to find them in the same individual and in such a stark way as you do in Fritz Haber,” Kean says. “Science is such an amazing field of human endeavor. Scientists learn incredible things, often taking heroic measures, making unbelievable sacrifices and achieving incredible results – whether it’s developing new medicines and technology or just helping us understand the world around us.”

Kean’s research uncovers many untold or mostly forgotten stories. What he hopes to capture with all of it is a sense of wonder. “I always think about what you see in little kids’ faces in museums as they look up at a dinosaur skeleton or a blue whale model or as they learn how a rainbow works,” says Kean when asked about what draws him into science writing.

“My hope is to use my writing to tap into that innate sense of awe and wonder about how the world works and bring people back to that state – when they were wowed as little kids by some scientific thing that they learned. Science captures it better than any other field I know,” Kean comments.

In his own childhood, Kean describes how his mom gathered mercury from broken thermometers for him to examine. “I always thought mercury was a cool, interesting substance, but when I learned about its amazing history, that got me thinking about the rich stories behind science.”

He returned to this thought about halfway through college when he became exasperated with his early lab adventures. “I realized that temperamentally, I was just not cut out to be in a lab,” he says. “I was a little clumsy with the equipment and would break things, but more than that, I just wasn’t happy there in the way that a lot of my classmates were.” Being a science writer was the best way to be involved with and learn about science while promoting the amazing work of scientists “without having to do it myself,” Kean says. “All of the fun, none of the frustration.”

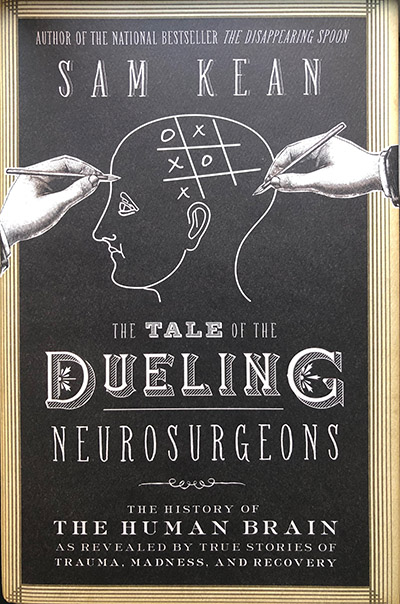

This eventually led to Kean’s first book, The Disappearing Spoon: And Other True Tales of Madness, Love, and the History of the World from the Periodic Table of the Elements, which was published in 2010. Days spent combing through archives and digging into historical records yielded a limitless harvest of fascinating facts such as why Gandhi hated iodine, how radium nearly ruined Marie Curie’s reputation and why gallium is the go-to element for laboratory pranksters (though solid at room temperature, gallium is a moldable metal that melts at 84 degrees Fahrenheit, so a classic science prank is to mold gallium spoons, serve them with tea, and watch guests recoil as their utensils disappear).

Thirteen years, five books, many magazine articles, and numerous interviews later, Kean is deep into a sustainable publishing career. His work has appeared in The Best American Science and Nature Writing, The New Yorker, The Atlantic, Slate and Psychology Today and has been featured on NPR’s “Radiolab,” “Science Friday,” and “All Things Considered,” among other shows. In 2019, he added The Disappearing Spoon Podcast, which is sponsored by Science History Institute and devoted to overlooked, surprisingly powerful stories from the past that didn’t quite make it into conventional history books.

“I get to jump into a lot of different fields and find that I’m constantly learning new things,” he comments. “My new book delves into experimental archeology. In developing it, I am out observing things in the field and traveling all over the world going to different sites and talking to different scientists.”

To explain experimental archeology, Kean shares as an example a piece of bread from King Tut’s tomb. “Suppose that archologists find such a thing,” he says. “To know what it actually tasted like, they go to great lengths to find the ancient grains that the Egyptians used, grind it the same way, bake it in a clay oven and eat it. This method of archeology brings the past alive in a way that traditional approaches don’t accomplish quite as well. You can learn amazing things from conventional archeology, but this sensory-rich experience gets at the past in a different way.”

Kean has enjoyed many novel experiences on the trail of writing this book. “I’ve gone to England to taste an authentic Roman banquet. I sailed the South Seas on an ancient ship that archeologists reconstructed to learn how people would have traveled thousands of years ago from island to island. I’ve watched the replicas of Medieval catapults in action as we hurled bowling balls hundreds of yards. It’s been a lot of fun to see all the cool things that archeologists are doing,” he comments.

In equal measure, Kean is impressed with the work of the SLAS community and how the automation process has changed the lab work he once found so frustrating. “Lab automation eliminates some of the drudge work that I frankly didn’t like a whole lot when I was working in a lab,” Kean says. “I think that I would feel a little different about it if some of these automated systems had been in place when I decided to go into writing instead of science.”

From his early experiences, Kean draws advice for others. To those seeking or tweaking a career path, he says: “Consider an apprenticeship in a new area. Go work in a lab. Get an idea of what the day-to-day life is like. For me it was good to get out there and realize that lab life wasn’t for me, but I still loved the field.”

To all walks of life sciences Kean recommends learning about the history of a particular field. “I think it will enrich your science. When you get a broader perspective, I think that you can appreciate it more and it might spark new ideas as well. There’s a tendency in science, where there is so much to know, to focus on the last few years of a field and neglect that area’s history,” he concludes.