September 9, 2013

Staying true to scientific discipline while leveraging every ounce of the technology surrounding it is Andrea Weston's modus operandi. She is not afraid of the next innovation – particularly when she has a hand in it.

2013 SLAS Innovation Award winner Andrea Weston, Ph.D., offers counter-intuitive advice for dreamers: Embrace the naysayers.

"If you are the type with your head in the clouds – and this is me – I recommend that you reach out to people who are grounded in reality," explains Weston, who works for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Wallingford, CT, as a senior research investigator. "I used to think of them by many names – naysayers, devil's advocates – those people who are always telling you why something won't work. It took me a while to understand that those are the people with whom you need to connect. Innovation comes from the combination of dreamers and realists. I need to hear why something won't work in order to fully appreciate the hurdles that must be overcome so that we can push forward in a systematic fashion to make it work."

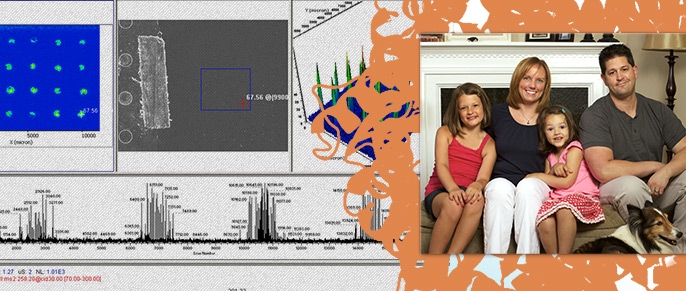

A sage observation from the lead author of "Making a Quantum Leap in Mass Spectrometry Throughput: Applying the NextVal MassInsight Technology to Monitor Cytochrome P450 Enzyme Inhibition in Human Liver Microsomes." This SLAS2013 presentation asserts that mass spectrometry has evolved as an indispensable tool used at multiple stages in the drug discovery pipeline. It addresses the challenges of applying this technology to high-throughput screening (HTS) of large compound libraries, given the need to purify samples prior to ionization.

Weston and a multidisciplinary team at Bristol-Myers Squibb partnered with Nextval to evaluate a high-speed, high-throughput (HT) platform through which mass spectra can be generated from acoustically printed arrays of samples as complex as cellular lysates. The team used this technology to leverage acoustic dispensing technology to rapidly print accurate, nanoliter volumes from microtiter assay plates onto addressable arrays coupled to a direct surface ionization approach which utilizes a matrix-free silicon substrate.

"I think the visibility of an award like this has attracted attention from many angles to the potential of mass spectrometry HT technology. When vendors and industry suddenly focus on a technology, it draws the resources and energy it needs to propel it to the next phase," she continues. "That next step will be to determine how to commercialize and implement the technology to add value."

The 2013 SLAS Innovation Award opened several doors for Weston, from the opportunity to travel and present her paper at the 2013 SLAS Asia Conference and Exhibition, held June 5-7 in Shanghai, to a chance to join the judging committee for the SLAS2014 Innovation Award.

The trip to Shanghai was eye-opening for Weston, who had not traveled there before. "The conference was an interesting snapshot of how SLAS is growing in China and how the scientific community is really taking off. It was valuable to me to see the position of the Society and science in China," she observes. "One thing that struck me was that despite how different China is culturally, I met many people who were able to transverse the culture through science." Part of this she credits to SLAS' work in Asia.

"SLAS is such a strong community around this portion of the industry. It's such a large group, but still very much a cohesive and well-organized community," Weston continues. "One of my colleagues, Jonathan O'Connell, Ph.D., has been very involved with SLAS. Through him, I have become very engaged and I'm very impressed by the Society and how it brings this community of professionals together." O'Connell is director of lead discovery and lead profiling at Bristol-Myers Squibb and a member of the 2013 SLAS Scientific Program Advisory Committee.

Weston has always been attracted to technology and research, describing them as continuous threads woven into her career. She counts herself as fortunate to have worked in several multidisciplinary laboratories with tech-savvy researchers.

Of her past work with Michael Underhill, Ph.D., at University of Western Ontario (UWO; London, Ontario, Canada), Weston says, "He always looked at new technologies to develop better HT assays."

It was the same when she worked in the laboratory of Leroy Hood, M.D., Ph.D., president and co-founder of the Institute for Systems Biology in Seattle, WA, and scientific advisor for SLAS' Journal of Laboratory Automation (JALA). "Lee Hood passed along advice that he received early in his career. First, always let the biology drive the technology. He also adds that if you really want to be at the leading edge, develop new technology that addresses fundamental biological challenges. He always had that technology mindset. In research, part of our job is to find the next cutting-edge technology that pushes the boundaries of what we can do. I feel that I have always aligned with that philosophy."

Before Underhill and Hood filled Weston's thoughts with research, she was med-school bound. "I loved science. I loved the challenge of the medical profession, its impact on people's lives and anything to do with the human body," she says.

A third-year class during her undergraduate years at Brock University in St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada, led her to a neurobiology course that, at first, did not seem thrilling. After the first session with Professor Joffre Mercier, Ph.D., however, she held a different opinion. "He would explain concepts such as the action potential, and you would leave class feeling as if you had attended a captivating movie," she enthuses. "He is passionate about his subject and has an engaging method of teaching." When the opportunity to work on electrophysiology in Mercier's lab came up during her fourth year, Weston seized the chance. "That was when I began to recognize scientific research as a path for me," she continues.

The project involved recording excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) from the deep abdominal muscles of a crayfish. "We used a lot of invertebrates. It was fun, but it didn't have a lot of applicability," Weston explains.

Still intrigued by that fourth-year venture into scientific research, she chose to attend the UWO and work in Underhill's laboratory. At that point, Underhill and his lab were so new, Weston says, that they worked out of boxes for several weeks after she arrived.

"Underhill is a phenomenal molecular biologist. He taught me everything I know about molecular biology. When I look back at that time, he had a fairly modest Canadian research grant and one grad student. He put a lot of energy into training me. It was a period where we both grew our careers," says Weston, who noticed early on the importance of mentors and their influence on her career.

"During grad school, when I was discussing my prospects for writing my thesis with the review committee, they asked me to stay and consider doing a Ph.D.," she continues. "I was having so much fun and learning so much, it wasn't a hard decision. I stayed for another three years. It was a productive time for me and my supervisor, who was able to grow his lab during that time."

Weston did eventually apply to medical school. In spite of some successful med-school interviews, the post-doc opportunity in Hood's laboratory in Seattle seemed too good to pass up.

"I decided that I was not going to do anything but go and work with Lee Hood!" she states, adding that she has no regrets about veering into research science. "I was so excited and energized by research opportunities, I couldn't entertain anything else. This is where I am supposed to be. I feel that I can help patients more from the medical research perspective," she explains. The rich environment and the newly designed institute included world-class scientists and Hood's new, unique views on multidisciplinary research. The entire time period inspired Weston, from the discussions about what systems biology is to the launch of several ground-breaking publications. Editor's note: Both SLAS' peer-reviewed, scientific publications, the Journal of Biomolecular Screening and JALA, began publication in 1996 during this exciting time in the field.

"At that time, around 1999, Lee was just launching his new institute, and they were contributing to the sequencing chromosome 14," she says. "He had a hand in so many areas, and they were such huge areas. Their plans were exciting to me."

Weston worked on multidisciplinary teams to model transcriptional regulatory networks. "We used biology assays as well as some computational and engineering savvy to put together models and then iteratively tested those models that define how transcriptional regulatory networks actually operate," she says.

In 2003, she pulled herself away from the Institute and relocated to Connecticut with husband, Chris, and decided to change course. "I was curious about industry. Not enough to drop academics, but enough to learn more about it. I found a post-doc position at Pfizer in Groton, CT, in developmental biology that looked at molecular mechanisms governing the toxicity of heart development. It was a change from what I was doing at the Institute, but it kind of brought me back into developmental biology, which was the focus of my Ph.D."

For Weston, it was the best of both worlds. "I was able to conduct an academic project while still working in industry. I felt like a kid in a candy store. I had access to unprecedented resources and capabilities, but still had a project that was academic. It was applied, but there was still support for it being an academic project," she explains, adding that she continued this for the next three years.

"I did like the industry setting. It worked for me," she reports. It also gave her an opportunity to eventually join the team at Bristol-Myers Squibb, a move that opened the door to the latest technology.

"Coming from a background with an intense research focus, to an HTS group, I had some reservations. I thought that initially, it might be too technology-based and less science-based. Certainly during the interview, I didn't get that feeling at all. Six years later, I would say that science drives the decisions around the technology," says Weston, who accepted the position because she liked the idea of being able to leverage HT technology. Weston attributes this steadfast commitment to science to her two key mentors at Bristol-Myers Squibb, Jonathan O'Connell, her former boss, and Martyn Banks who is her current manager and executive director of the department, stating that "both Martyn and Jonathan are firm in their conviction that science should prevail over pragmatics." Weston asserts that this guiding principle combined with their unwavering support and enthusiasm for new and innovative ideas underlies the success and culture of the HTS group. "I've been overwhelmed by this team's ability to exploit technology in a way that delivers true value to Bristol-Myers Squibb programs"

She sees a connection between her position at Bristol-Myers Squibb and that crayfish project from her undergraduate days. "In my role now, we support a lot of different targets. In addition to HTS, I oversee cell line development for much of research and development at Bristol-Myers Squibb. Right now we're developing a lot of ion channel cell lines," she says. "The whole thread of electrophysiology and ion currents from my fourth-year project has really come back to my work with a vengeance! It's a subtle thing where I can relate my early work in science to what I do now."

The strong molecular background from her Ph.D. work supports her current work as well. Weston observes that a lot of molecular biology has become kit based. "You open up a kit and follow steps one, two, three and four and you have your outcome. Back when I was doing my Ph.D., Dr. Underhill taught me the basics and the details of molecular biology, and I find that it really plays into most of what I do both on the cell-based assay side and in cell line development. We have an interface between molecular biology and HTS, some of which we haven't explored yet."

When not discovering uncharted territory in the lab, Weston is likely to don a parka and dig into the great outdoors. Her husband, Chris, as well as the couple's five- and eight-year-old daughters, Paige and Sydney, fill most of their time with cold weather activities. "Being that we are Canadian, we love winter sports," she says, adding that the family enjoys skating, skiing and hockey. But summer is not an idle time; they fill those months with bikes and running shoes. "I have done a few races and am now training for my first half marathon," Weston says. "I am focused on increasing my time and distance, while my eight-year-old Sydney rides her bike next to me and acts as my cheerleader."

She also spends time engaging in her "mild obsession" with social media. Her daily habit includes reading a few favorite blogs: "Mile Markers" by author and runner Kristin Armstrong; "Zen Habits" by author Leo Babuta; "Where Science and Compassion Meet" by Stanford University health psychologist and lecturer Kelly McGonigal, Ph.D.; and "Ask the Lab Man" by SLAS Education Director Steve Hamilton, Ph.D. "The proliferation of social media is fascinating. It is changing the way that we communicate," says the avid reader who also takes time to read the works of F. Scott Fitzgerald, one of her favorite authors, and books from the Best Seller list.

"When I was younger, I worked all the time. It was like stepping on the gas pedal and never pausing to take my foot off. I worked weekends and everything. In the last couple of years, I have found that a complete shut down and not thinking about work actually makes me more productive and effective. I recommend that people take breaks and do things they enjoy," she advises.

In spite of this devotion to disconnecting, Weston laughs about her lengthy "to do" list. As she quoted Michelangelo in her thesis: "May I always aspire to do more than is even possible to accomplish." Admitting that she had to get comfortable with not getting everything done, Weston ruthlessly prioritizes her list throughout the day to groom it to a manageable amount.

Topping the family's "to do" list these days is supporting her husband's recent decision to leave the pharmaceutical industry for teacher's college. "He is preparing to teach high school science," she reports. His most recent assignment was a volunteer opportunity to teach science in the couple's eight-year-old daughter's class. At this point, both daughters like science, but haven't followed it with their parents' passion – yet. Weston says her older daughter is more drawn to math, "and my younger one wants to be the Easter Bunny!" she laughs, adding that it has something to do with distributing eggs and happiness.

Regardless of what undertaking one pursues, Weston says that perseverance is the main principle to follow. "I don't know anyone in science who hasn't wanted to throw in the towel at some point! Perseverance is what gets you through and leads you to success," she concludes.